Politics – Mesrena Elyoum

The political assumption in these times of the Covid-19 pandemic is that incumbent governments could look confidently at their chances of re-election based on the principle that the people tend to re-elect governments in times of tumult.

The question is, is that changing? Are the expectations of voters changing from the government as a security blanket to a more critical analysis of the role of government, the mistakes that have been made in pandemic management, vaccine rollout, quarantine?

Incumbency has had its benefits

From the moment the pandemic hit our shores, we’ve seen almost rock star approval ratings for state premiers and for the PM. Three state governments have been re-elected in that time. In Queensland in October last year, Anna Palaszczuk’s Labor was returned with an increased majority. In Western Australia in March this year, Mark McGowan’s Labor was returned with a spectacular majority in both houses with the Liberals in the state all but wiped out. The Liberal government was returned in Tasmania with its majority untouched.

The Morrison government finds itself in a pitched battle for a 2PP preferred lead in polling, with the vote neatly spread at 50-50 or perhaps 51-49 Labor’s way. The polling indicates five bobs each way, or in the language of psephologists, too close to call.

The first thing to note is that there has been a different voting projection in the federal sphere than we’ve seen in the states where incumbency is king. The battle at the federal level is much tighter. The Morrison government governs with a majority of one in the House.

The second is that the Prime Minister’s ratings have taken a whack from those security blanket days where JobKeeper was rolled out and JobSeeker more than doubled. Scott Morrison continues to lead opposition leader, Anthony Albanese by considerable margins in their respective approval ratings and as preferred prime minister but the gap is narrowing.

Let’s look at the possible timing of the next federal election. Had the vaccine rollout been successful with approximately 70 per cent of Australians being fully vaccinated as of September or October, we could safely have expected a November or December federal election.

Peering into the future, what we can predict with a reasonable amount of certainty is that the vaccine rollout will improve. Let’s face it, it couldn’t get much worse. The Pfizer vaccine will be more readily available as we move forward, with more than a million doses per week available by August. Moderna will come online in Australia and Novavax, with some impressive results in its Stage 3 clinical trials, should come into the mix as well.

When the government’s anointed vaccine, Astra-Zeneca ran into problems leading to restrictions on who may receive it, the early election strategy went out the window.

The timing of the next federal election is now based on when Australia might reach that fairly safe position of having approximately 70 per cent of the adult population fully vaccinated but not to the point where the country opens up again.

The politics will change again at that point

There will be hues and cries from those who for one reason or another have declined to be vaccinated. The vaccinated will be able to move freely around the country, catch flights, and travel overseas. They will have employment opportunities at least in various fields that will not be extended to the unvaccinated. Freedom of movement and association whether it is by government edict or more often, by rules set by corporate Australia and the business community will draw a sharp line between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. These may well extend to the simple act of entering licensed premises or going to the movies, the theatre, or indoor sports.

The vaccinated will have some form of digital passport permitting entry and those without will be told not to bother.

When the country does finally open up, there will be a lot of Covid-19 infection and those who are unvaccinated will be at risk. It will be a time of great sound and fury and one suspects not a sensible time to have an election.

We’re looking at around 20-25 per cent of the Australian electorate who will remain unvaccinated by early next year. Many will carry a deep sense of grievance against the government, indeed any government. When it comes to voting behaviour, will they head for the plethora of minor and single-issue (anti-vax) parties now assembling and if so, how will their preferences fall?

That is an unknown known to quote the late US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld. But in the knowable category, the election will be held prior to those heady days kicking in. We are probably looking at a date in February or more likely, March 2022 but the timing relates more to vaccination rates rather than an ideal date on the calendar.

As Kevin Rudd found in his GFC response in 2008-09, throwing money at Australians never hurts one’s chances at the ballot box.

At that time Rudd enjoyed spectacular approval ratings but that did not last although he remained the preferred PM and Labor held an election-winning lead in 2010 when he was brought down by his own party.

Perhaps that old axiom of governments losing elections rather than oppositions winning them needs to be clarified with the preamble that unless the party room doesn’t step in the first place.

Labor’s and advertising and marketing teams have been burning the midnight oil of late. Morrison’s ‘Not a race, not a competition’ remarks which look and sound terrible, have been dragged out and edited against the more urgent approaches from other world leaders and pandemic managers.

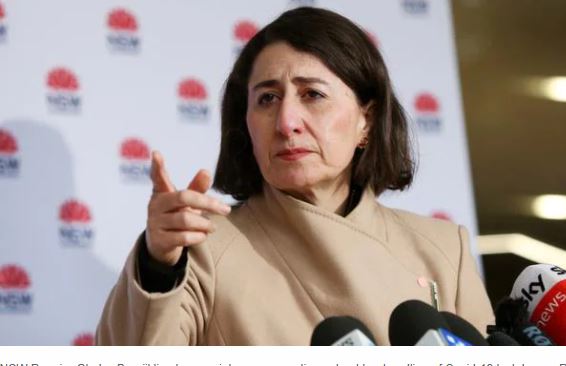

The period between then and now remains critical for the Morrison government. Should Sydney endure a long lockdown, through August and into September, there will be considerable focus on the mistakes the federal government has made.

The result of the election and how the government manages its re-election prospects will be determined over the coming weeks.